October 12, 2023

By: Danruo Zhong, Brie Reid, and Megan Gunnar

One of the most high energy things we do in life is to grow. To grow taller, our body must make new bones, muscles, tissues, and blood. When we grow rapidly, our bodies must assign lots of metabolic resources to the process of simply growing. Putting lots of resources into growing means that they might not be available for other bodily functions. One of those resources is iron. Iron is critically important for many bodily functions, including supporting brain health and development. Back to iron in a moment.

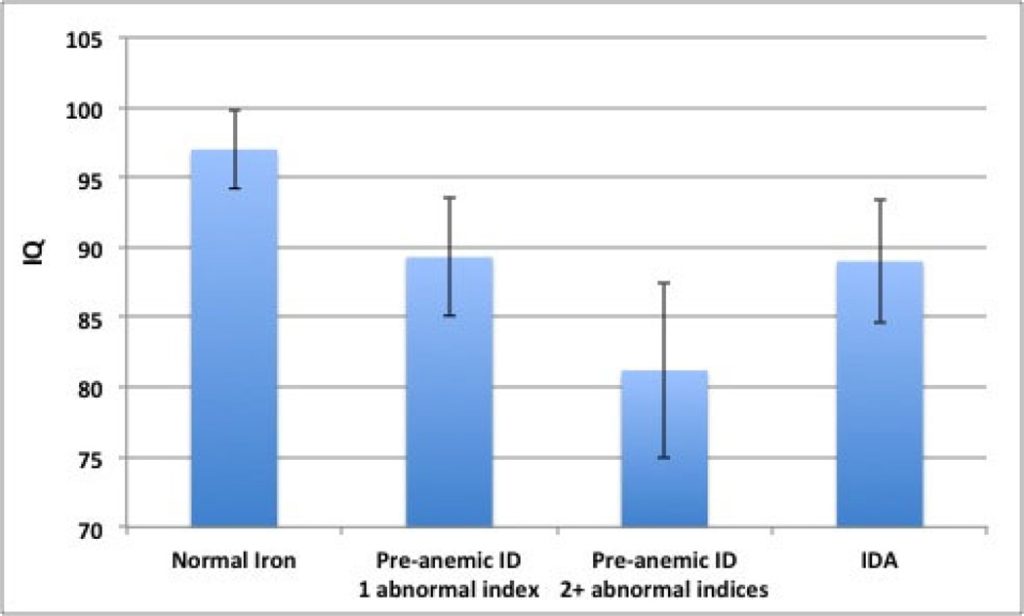

One way that children survive difficult situations is to grow more slowly if at all. Children who have started out their lives in institutional care are often shorter, but not thinner, than other children their age when they arrive in their families in the United States. They then begin to grow more rapidly than other children. This is called, “catch up” growth. We have been interested in catch-up growth for a long time. While, on the one hand, it seems terrific that the kids are growing rapidly, on the other hand doing so places demands on their bodies. Several years ago, our colleagues in the medical school at the University of Minnesota found that children who showed more rapid catch-up growth sometimes outstripped their iron stores and began to be a bit iron deficient. This probably doesn’t happen to children with adequate iron stores when they start a period of rapid growth, but children coming from institutions often have marginal iron stores at adoption. The research study showed that poorer iron status within a year of adoption, even if it is not at the level of anemia is associated with more problems in attention in previously institutionalized children by the time they are about to start school. Figure 1 below is from the paper we published in 2014.1

In that study, though, we could not trace the effects to rapid catch-up growth as we did not measure them over time. Recently, we used data from our Transition into the Family Study to examine whether height for age at adoption or rate of catch-up growth predicted attention problems when children were entering school. We found that height for age within a few months of adoption did not matter. What did matter was how rapidly they grew after adoption. Those who grew faster had more problems regulating attention when they were entering school. The results of these studies raise challenging issues for parents and medical practitioners. Should we try to slow down post-adoption growth or are their ways to making sure that we help the body have enough resources to rapidly grow both bodies and brains?

- Doom JR, Gunnar MR, Georgieff MK, Kroupina MG, Frenn K, Fuglestad AJ, Carlson SM. Beyond stimulus deprivation: iron deficiency and cognitive deficits in postinstitutionalized children. Child Dev. 2014 Sep-Oct;85(5):1805-12. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12231. Epub 2014 Mar 5. PMID: 24597672; PMCID: PMC4156571. ↩︎