October 15, 2024

By: Zach Miller

Previous research on how children’s biological systems respond to stress, specifically the stress hormone cortisol, have helped us to understand the impact of stress on our bodies. Related studies have also shown us how social support from a loved one can reduce this stress response in children. The Brain Study of Stress & Social Support was developed to bring neuroscience into the mix and try to paint a picture of what is happening in the brain when children experience stress. This study is a collaboration between the Gunnar Lab and the research laboratory of Dr. Katie Thomas. Thanks to over 200 families, this study has collected data on how children’s brains react to stressful situations and how those reactions may change depending on whether they have a parent, a stranger, or no one with them.

Data analysis and interpretation has been ongoing for the Brain Study of Stress & Social Support in the Gunnar and Thomas labs since we completed data collection late last year. We continue to delve deeper into the data to better understand how social support changes how our brains respond to stress. We had hypothesized that the amygdala, a region of the brain that is a major processing center for emotions, may show differences depending on what kind of social support children had during the study. The amygdala is usually very active during stressful times and while experiencing negative emotions and we predicted that the support of a loved one would reduce this activity, signifying a reduced response to stress in the brain. Analyses appear to support this hypothesis, as we show in the brain images below.

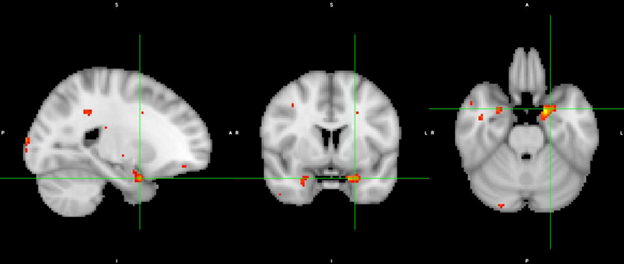

These images both show a side, front, and bottom view of the brain, with the green crosshairs pointing to the left amygdala. The first image, Figure 1, with red/yellow spots shows the difference in brain activity during the stress test between children who completed the test alone versus those who completed the test with a parent present. The larger and brighter spots on the amygdala show us that that region of the brain is more active in the children who were alone during the stressor.

The second image, Figure 2, with blue spots shows the difference in brain activity during the stress test between children who completed the test alone versus those who completed the test with a stranger present. We can see that the spots in the amygdala have almost disappeared, suggesting that there is not much of a difference made by having a stranger with you during the stress test.

Together, along with further statistical analysis, these images suggest that the relationship between a child and their supporter makes a difference in how they respond to a stressful moment. In order to have a greater effect, supporters need to be loved ones with whom they are familiar. Although this may seem intuitive, this type of research that brings together different testing modalities greatly helps researchers understand the nuances of our stress responses and builds a stronger base upon which future research can be built.

We would like to thank all the families for their participation and support in these research endeavors. Without your help, none of this would be possible! A related study, the Brain Study of Peers, Parents, and Stress, which includes friends as social supporters is ongoing. If you and your 11-14 year old child are interested in participating, please read more here and contact the study at socialbuffering@umn.edu or 612-626-8949.