In 2017, a group of Black Men and Minneapolis Police Officers came together to discuss the issue of distrust between Black men and the Police. Over the course of a year, we came to the following shared understanding and beliefs on how we see the problem and the solutions. Community group members were Joseph Anderson, Guy Bowling, Brantley Johnson, Justin Terrell, Michael Walker, Damian Winfield, and Corey Yeager. Police members were Charlie Adams, Jon Edwards, Dave O’Connor, Steve Sporny, and George Warzinik. The process facilitator was Bill Doherty of the University of Minnesota.

Everyone word of this document was generated, debated, and agreed upon by the whole group.

Narrative Outline

1. The Origin Story – How a table of black men and police officers came together to talk about distrust between our communities and ended up talking about how to build safe communities.

2. How we see the Problem – Why there is distrust between Black Men and Police Officers

3. Core Beliefs – What we believe

4. Imagine a Safe Community – Our aspirational vision for safe communities

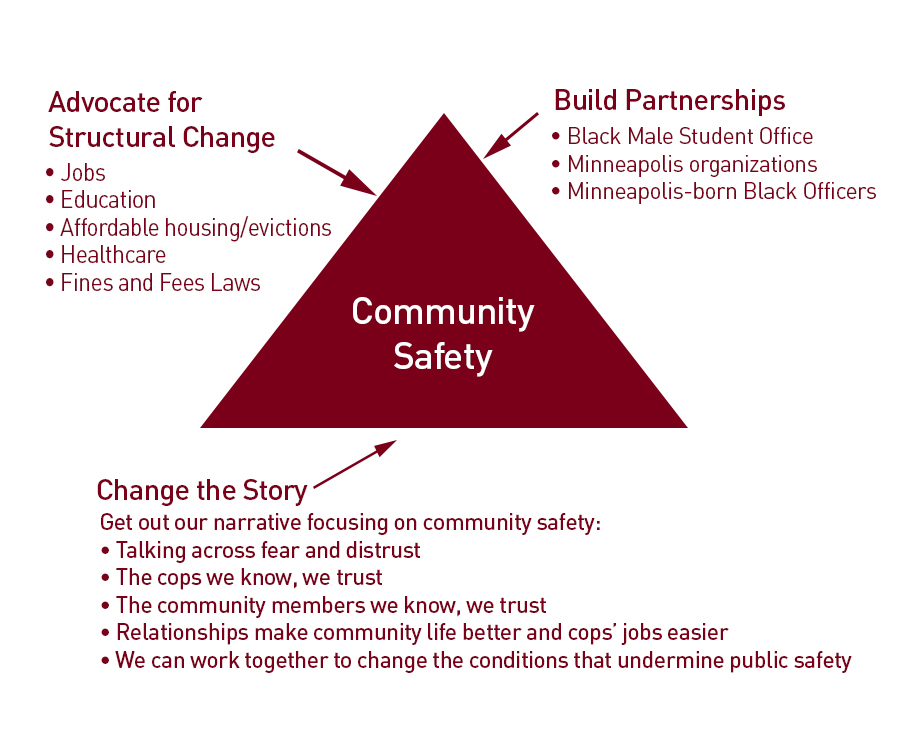

5. Our Theory of Change

1. Origin story

The project came out of a conversation between Bill Doherty, of the University of Minnesota’s Citizen Professional Center, and Guy Bowling, director of the FATHER Project in Minneapolis. Bill (a White man) and Guy (a Black man) had worked together on community projects for many years. Their conversation occurred when the community was reeling from the death of Philando Castile after a traffic stop by a police officer in Falcon Heights. Guy posed the question about whether Bill’s Families and Democracy model could be applied to the problems between Minneapolis police and Black men. This approach focuses on grass roots relationship building prior to action steps, rather than traditional top-down programming.

The basic idea that emerged was that a small group of police officers and Black men from the Minneapolis community would meet frequently over at least a year to develop relationships of trust and then decide on joint action steps.

Bill and Guy knew they could personally recruit the Black men from the community, but neither had ties to the Minneapolis Police Department. So Bill consulted with a well-connected friend who suggested starting by running the idea past Bob Kroll, head of the police union. Bill sent Bob Kroll an email in January 2016 and immediately received a positive response and an invitation to meet Officer Dave O’Connor, a union leader and public engagement officer. That month Bill met over coffee with Dave and his partner, who were enthusiastic. Dave then discussed the idea with his colleagues and superiors, and got green lights. Finally, Bill contacted the Chief Harteau who met with him along with her Community Liaison Sherman Patterson. The Chief approved the idea with great interest, and entrusted Sherman Patterson with setting up a process of selecting the officers.

The group to be recruited would consist of five officers (one Black, five White) and seven Black men from the community. (one White officer subsequently dropped out and was replaced by another Black officer.) Officers were nominated by a group consisting of Deputy Chief Arradondo, Sherman Patterson, Dave O’Connor and Bill Doherty (Bill had final screening authority). Once a group was nominated, we met with the Precinct Inspectors to get their buy in and willingness to approach the nominated officers. The Inspectors were uniformly positive about the project and then recruited their officers. The community members were nominated by Guy Bowling and Bill Doherty (one was nominated by Sherman Patterson), and interviewed by different combinations of Bill, Guy, and Sherman.

The group began its biweekly meetings in January, 2017, with this goal: to forge connections between police officers and African American men that can lead to better partnerships for community safety and law enforcement. With Bill facilitating, we used a process of building relationships through personal storytelling, then opening up challenging topics, and deciding to create a common narrative to describe who we are, how we see the problem, what we envision for a safe community, and how we act together to bring about change.

2. Why is there Distrust between Black Men and Police Officers?

There is a history

of Police being used to enforce and protect an unjust status quo.

This history goes back to slavery, slave patrols, and Jim Crow. We see it

continuing today with inconsistencies in the criminal justice system and with

laws and policies that have led to mass incarceration. Historically, Black

people have been seen as threats to be controlled, with Police being one of

many mechanisms of control and protection for the powerful. These traditions

have developed a culture that produces lifelong distrust between us.

Police and Black men lack a shared understanding and relationship with each other.

Without a relationship between the two groups, we both become the “Other” who is seen as a threat. We ignore the innate values and beliefs we share in common, including the value of safe communities. Therefore, the only way to build trust is by moving into relationship with each other to tackle the issues that undermine community safety.

There are underlying issues (poverty, family instability, housing, education, health care, and others) that undermine the ability to build relationships for community safety.

Simply inserting Police officers into stressed, resource-challenged community without addressing underlying problems sets up both groups for bitter, fractured relationships, and makes safety harder to achieve.

There are common, dehumanizing, media-driven stories about each of us (both Police and Black men)—that we are violent, guilty, suspicious, uneducated, and have broken families.

These stereotypes dehumanize us and pit us against each other, undermining trust and the ability to work together on common goals.

3. Our Core Beliefs

As a Community of Black Men and Police Officers, we believe:

- That we have a common goal of community safety.

No one wants to live in fear and everyone wants the best for their loved ones. Our common goal of community safety is based on wanting to feel safe and secure in our homes, neighborhoods, work places, and the communities we visit. This shared goal of community safety drives everything we want to do together.

- That we can’t police our way out of the problem of lack of community safety.

Police by themselves cannot create safe communities. Rather, ordinary people do–family members, neighbors, co-workers, classmates, and community leaders. Trust and a sense of connection between people are what make communities safe, and these require resources that are often lacking. By the time people call the police, community safety and trust are already threatened or violated.

- That ongoing police training, while necessary, is not the solution.

A well-trained police force is essential, but focusing on training is too limited a response to the challenges facing community safety. Our local governments and civic leaders must invest resources in communities in a way that fosters more trust, connection, and economic stability. People feel safe and avoid crime when they can work, find good housing, educate their children, and feed themselves and their families. Investments in training police officers should be framed as one part of a much larger solution, and not just as a visible response to social pressure.

- That we each catch the blame for lack of community safety, and that we have to get closer together to address the problem and make a difference.

As mentioned, Black men and Police are feared and stereotyped. Black men are seen as dangerous and a threat to be controlled. Police are seen as dangerous and as a force to control people. There is immense power for change if both sides could bust these stereotypes and work together for community safety.

- That people in power (those who make decisions and have lobbyists) think they know best and share no blame for the problems facing us and the community.

They are held to a different standard and often tell distorted stories about us through the media. They are disconnected from both the Police and the Black community, and they derive benefits from the current situation. We want to build relationships with people in power, so that they can know us and we can know them, for the sake of joint solutions.

4. Imagining a Safe Community

We imagine a safe community:

- Where people are in relationship with each other and connected through a sense of community

- Where people watch out for one another

- Where the neighborhoods are safe and clean for kids and families

- Where bad things still happen but justice is restorative and healing, and not just focused on punishment

We imagine a safe community where policing is:

- Truly community based: they are your family, friends, and neighbors, and what happens to the community impacts them

- A profession that is trusted and honored by the community, and

- Officers aren’t feared but seen as resources

We imagine a safe community where Black men:

- Are free to be themselves and accepted for who they are

- Have no barriers to their success – they have housing, employment and the resources to address basic needs and social aspirations

- Can go anywhere without fear

- Feel an ownership of their lives, their families, and their communities

We imagine a safe community where the wealthy and powerful:

- Feel a stake in the success of people with less wealth and power

- Personally know people in the community

- Use their wealth and power so that others can have wealth and power

5. Solutions and Theory of Change

Two Common Narratives and Our Alternative One

The current public debate focuses on two competing narratives, one focusing only on police accountability and the other focusing only on personal responsibility. Although each narrative has valid points, both are limited and keep us stuck in finger pointing. We are offering something broader and bolder: a narrative of partners for community safety.

| Police Accountability Only | Personal Responsibility Only |

| This narrative argues that a set of policy changes that can hold Police accountable to a high enough standard that will prevent Police misconduct. | This narrative argues that Black men and the community need to bear the responsibility for crime and thereby avoid Police use of force. |

| Examples: Oversight boards, body cameras, changes to policies and procedures, and ongoing bias training. | Examples: Call for “law and order” and cooperation with Police. Accusing the community of not emphasizing civilian violence in the same way it responds to state violence. |

| Partners for Community Safety |

| This narrative focuses on a shared goal of community safety. All people want to feel safe and free. Rather than focusing on punishment, the community and any state agent who engages with the community is focused on the overall goal of safety. |

Examples: Officers who live, work and play in the community, and who are in proximity to the community and foster mutually respectful relationships. The Police Department and community partners work together to promote the necessary conditions for safe communities, including better housing, jobs, education, and health care. These changes benefit everyone – community and Police alike – because Police are part of the community and we all want safe lives for ourselves and our families.

Limitations of the Police Accountability as the Main Narrative: It’s not collaborative, often adversarial, leads to specific policy shifts rather than major cultural changes, does not address the larger forces that create unsafe communities — and many communities are still unsafe even if Police change.

Limitations of the Personal Accountability as the Main Narrative: Fails to recognize the larger forces that create unsafe communities, and doesn’t invite Police changes.

Advantages of the Partners for Community Safety Narrative: Police and Black men are allies to help the community become safe, developing closer relationships so that Black men feel safer with Police, Officers’ jobs are easier, and working together could lead to systemic changes needed for safe communities.