Divorce Outcome Research Makes State Take Note

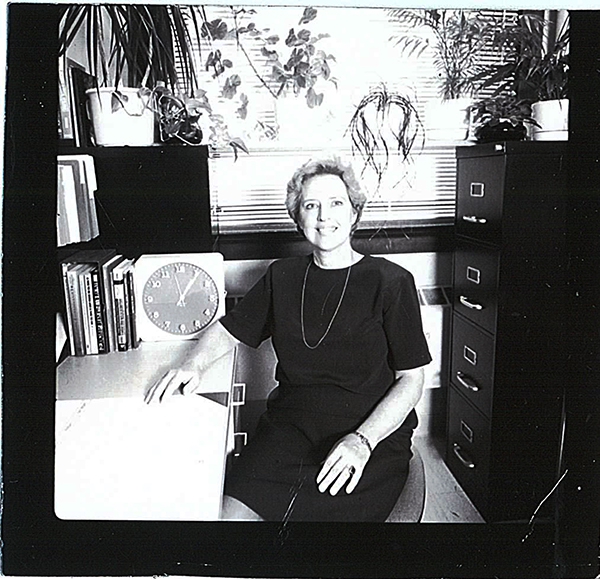

Dr. Kathryn Rettig, Professor in Family Social Science, has been taking a lot of trips to the house recently, the Minnesota State House of Representatives to be precise. Rettig has been involved in research about child support in post-divorce families. In fact, four of her last six refereed journal articles deal with the issue, and that says little about the total amount of time she has commit-ted to this research. One thing is certain, the Representatives have heard and are taking notice of her findings and her ideas about changing the Minnesota child support situation. A House Bill put forth by Representatives Jean Wagenius (DFL-63B) and Kathleen Vallenga (DFL-63A) outlines the use of a new income equivalence worksheet. The worksheet was developed by Rettig, drawing on her research expertise, and Judge Mary Louise Klas, Second District Court of Minnesota.

The worksheet being considered is a tool originally developed for research which measures income adequacy in divorcing families where support of dependent children is of concern. It is based on the assumption that everyone is entitled to at least a poverty level income. This level of income acts as a common denominator for the income equivalence calculations and is considered an objective national policy standard on which many family policy decisions are based. Awarded for its scientific and practical merit by the American Council on Consumer Interests, the measure applies this methodology to a practical problem faced by families and family courts today. It asks the question: Do the two households involved have equivalent income? If not, then how much money needs to be transferred to attain equivalence?

Minnesota “requires either or both parents to pay child support in an amount determined to be in the best interests of the child.” Best interests means “enjoying a similar standard of living in each parent’s household (House Research Department Bill Summary, February 28, 1992).” The worksheet offers a way to calculate whether the two households have a similar level of living and how to adjust the household incomes to make the levels equivalent.

Rettig says this project, now in its sixth year, has been a joint effort since its inception. Its design and execution has been deliberately policy relevant. In addition to Rettig and her team of researchers from Family Social Science, involved have been the Ramsey County Board of Commissioners, District Court, the Minnesota Supreme Court Task Force for Gender Fairness in the Courts, and a number of community focus groups.

The goal of the project has been to evaluate the economic consequences of divorce for men, women, and children in Minnesota. Her research team has compiled and analyzed data on 1,153 divorce cases occurring in 1986 and has done follow-ups with a subsample of cases two and four years afterward. The research has many policy and educational implications as well as the scientific ones. Whereas it began as policy analysis research, it is also part of the process of policy development and implementation and has educational components.

The income equivalence worksheet is already being used in Ramsey County Family Courts as a decision tool for divorce decrees. Celvia (Dobbins) Dixon, a FSoS doctoral student, has been working with Rettig and Jean Bauer on a related project for some time. She is helping to develop a series of educational tools to be published by the Minnesota Extension Service. The publication is designed to help people calculate and better understand the expenditures they must account for when raising a child. The Midwest regional publication will be used by Extension Agents throughout 12 Midwestem states.

Through her various dealings with legislators, judges, lawyers, and divorcing parents, Rettig has learned a great deal about how Minnesotans think and feel about the issue.

“Everyone,” she says, ‘judges, attorneys, even parents, greatly underestimates or doesn’t understand, the real cost of raising a child. So many of the costs are hidden or taken for granted in ‘intact families.’ There are people, particularly fathers who owe a lot of money, testifying against this legislation, lots of non-custodial parents who have no intention of paying or being supportive.” Rettig also notes that her research indicates that people at the higher economic levels are just as likely not to meet their child-support obligations as those at the lower levels.

Rettig’s research and its policy and educational implications may change child support awards in Minnesota. It is her hope that taking a new look at these issues will help us understand the ways in which divorce is related to economic instability and the conditions underlying poverty in post-divorce families.

(Story originally published in the Spring 1992 issue of the FSOS Department newsletter, Interactions).